2025 will be remembered for forcing an uncomfortable question: what happens when the aid architecture collapses?

When USAID froze $27.7 billion in global funding, a wider unraveling followed. Aid commitments were slashed by the UK, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands. The Global Fund trimmed $1.43 billion already allocated for 2023-2025. Gavi secured $9 billion toward an $11.9 billion target, then watched the US Health Secretary announce they'd stop contributing altogether.

The impact could be seen by the naked eye: Stocks of HIV medication depleted, maternal health programmes ground to a halt and millions worth of malnutrition aid went to waste. To culminate an exhausting and horrific year, the Gates Foundation announced that it was the first year this century where child deaths increased.

Alongside plummeting figures around the impact of these cuts, there's been plenty of forward thinking talk. Zambia's President called it a "long overdue wake-up call," Rwanda's Kagame noted that "we might learn some lessons from being hurt." Many are preaching domestic resource mobilisation, public-private partnerships, and new financing models.

In 2026, leaders are looking to alternative and blended-finance mechanisms like social investing and carbon markets to fill the gap left by aid cuts. But one week into the year, the US withdrew from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), severing ties with international compliance markets and eliminating any US obligation to buy credits to meet climate goals. In one fell swoop, the world's second-largest emitter created a $10-25bn climate finance gap.

The gap isn't just about money though. With even less resources, now is the time to scrutinise what it really takes to fund self-sufficient solutions.

Here are five uncomfortable truths, spanning the unsexy infrastructure, mismatched burdens, and ground-level barriers that determine whether ambitious frameworks can deliver for the communities they're meant to serve.

Post-aid localisation means more than translating interfaces. Since 2018, Brink has supported over 400+ ventures across 53+ countries to access more than £60m in funding. The majority feature some form of tech implementation, and one common thread: technology that works in one environment doesn't automatically work in another.

Climate finance worth millions can't flow to Tanzanian communities because an AI model trained on North American forests can't recognise Miombo woodlands. In Senegal, a soil health project currently relies on a proxy model from Kenya to estimate carbon sequestration due to lack of local data.

This isn't just about software retraining - it's about the gap between global frameworks and local reality. If your monitoring system can't recognise what matters, you're measuring the wrong thing and climate finance flows get stuck in the middle.

We’ve worked with agricultural ventures in Rwanda that had to close early because asset lifecycle financing is consistently underfunded. This is the unglamorous but critical work of maintaining, translating, and adapting technology after purchase. When a shiny monitoring solution is only available in another language, it’s the smallholder farmers who miss out.

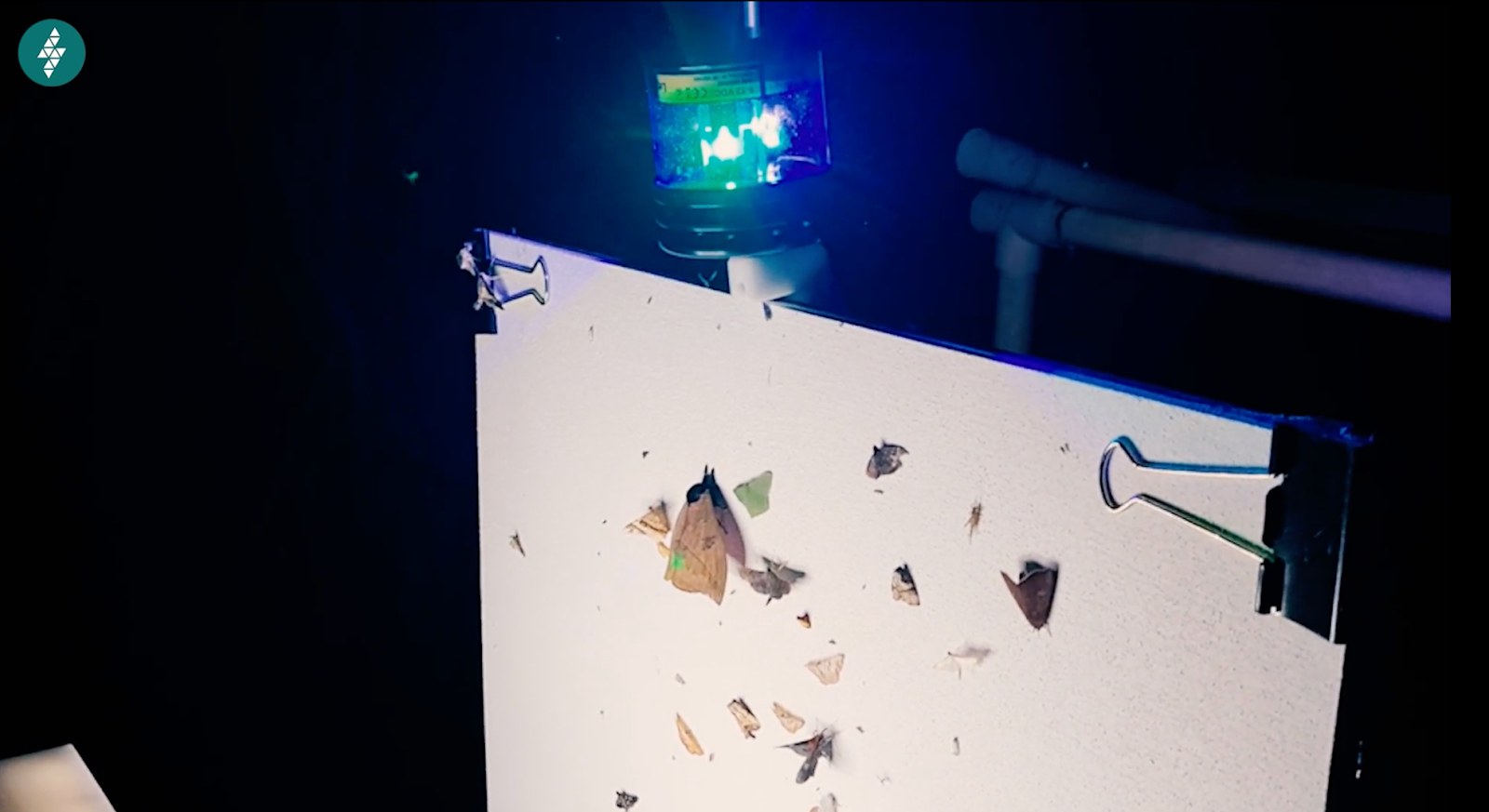

While manual monitoring is expensive and hard to scale, end-to-end technologies can provide the monitoring and reporting needed for projects to access credits. But these solutions rely on building supply chains that can maintain hardware without flying in parts and developing expertise among people who will actually use the tools long-term.

Post-aid climate finance can't rely on communities absorbing years of upfront costs while waiting for carbon markets to mature

You can't vibe-code your way around a broken sensor in rural Sierra Leone - the person who can fix it needs parts, training, and payment.

One approach is to co-design versions of existing tech directly in context. In Kenya, an existing UK biodiversity-monitoring system has been re-designed at 50% of the original cost. The final product is 5x smaller than its bulky equivalent, can be carried in a backpack and is just as manufacturable and fixable in Nairobi, as in London.

Another default has to be nurturing local talent. In Tanzania, local "AI Chapters" were established to train 50 young engineers capable of maintaining and refining the AI models described earlier (in order to rule out reliance on expensive foreign consultants).

Post-aid climate finance can't rely on communities absorbing years of upfront costs while waiting for carbon markets to mature. The money has to flow earlier to help vulnerable communities access and realise the outcomes down the line.

In Sierra Leone, rural poverty drives deforestation for firewood because the financial reward for cutting a tree is immediate, while carbon market returns take years. As a local expert told us: "people need to be able to make more money from a living tree than a dead one. Otherwise this just doesn't work."

Post-aid climate finance can't rely on communities absorbing years of upfront costs while waiting for carbon markets to mature.

Climate finance mechanisms need to restructure their timelines to match lived reality. If a model requires farmers to wait 5-10 years for payoff while they're focussed on affording their basic needs today, it will fail regardless of how sophisticated the satellite monitoring is.

Project Sapling tackled this temporal mismatch head-on by experimenting with "forward credits" (ex-ante). Drones and mobile apps verify that saplings are planted and surviving, creating a trusted record that allows them to sell credits before trees fully mature. This unlocks early funding to cover upfront costs and compensate communities sooner, aligning immediate incentives with long-term ecological health.

Those who receive the lowest share of supply chain value cannot be expected to absorb the prohibitive verification expenses required to participate in carbon markets. Likewise, essential intermediaries like cooperatives and NGOs cannot be left to navigate the market without support.

We’ve ended up with a shop window covered in pictures of forests— far easier to design for than the humans who are supposed to benefit from carbon markets. Either verification costs should be covered by those demanding compliance (and who profit the most), or we accept that carbon markets will systematically exclude the communities who need them most.

Those who receive the lowest share of supply chain value cannot be expected to absorb the prohibitive verification expenses

The same dynamic exists in export markets. In Colombia, growing cocoa is a legal alternative to cultivating coca, but complying with the EU Deforestation Regulation’s requirements is expensive and technically difficult. We supported FOLIA to develop a digital platform integrating satellite data with farm boundaries to automate the relevant deforestation risk reports. We found that farmers are willing to provide data, but the system becomes extractive if it adds financial strain rather than facilitating market access.

The tech provides a solution that works — but who should bear the cost?

If your plan relies on government adoption, your solution needs to be cheap and low-risk. If your plan relies on philanthropic foundations, you're competing more than ever before to demonstrate scalability. Commercialisation is the inevitable endgame, and that shifts everything.

In our recent call for solutions on the Frontier Tech Hub we received incredible pitches on carbon credits - from Gabon and South Africa to Mexico and Peru, some explicitly exploring blockchain ledgers for carbon markets. But in the post-aid world, we can't fund ideas without clear commercialisation routes as easily as before.

We all want to live in a society which doesn't suffer the devastation of the climate crisis, so it's time for the public and private sector to work hand in hand. The latter must own its responsibility more, while the former designs mechanisms that allow it to happen in practice. Models like the Climate Finance Partnership use public funds as 'first loss' guarantees to insulate private investors, providing the funding infrastructure that helps entrepreneurs survive the “valley of death.”

The timelines for catalytic capital must match the reality of what it takes to achieve viable models. Even after five years, many successful 'commercial' ventures won’t achieve full cost recovery, instead maintaining 40-60% earned revenue with ongoing grant support. The pathway looks less like independence from aid and more like strategic hybrid resilience.

The decisions to cut aid funding have been devastating. The only (very thin) silver lining is that they have forced us to confront two gaps: one between policy ambition and implementation reality, and one between public responsibility and private interests. We should be designing carbon markets for the smallholder farmers who need them most, and sophisticated financial architecture doesn’t equal opportunity for those on the ground.

Tech transfer is never automatic - what worked elsewhere will fail until adapted for local ecosystems, and made affordable to maintain. Temporal mismatches doom participation when payoff is years away but needs are immediate. Verification burdens land on the wrong people when compliance costs stay with those least able to pay. And commercialisation only works if it builds sustainable capacity, not new dependencies.

Have you seen these barriers in your work too? We want to see new avenues for development finance evolve beyond sophisticated global frameworks to become non-extractive infrastructure that actually works where it's meant to work.