In 2023, overseas development aid totalled $243bn. In 2024, it fell 10%. This year, it’s projected to fall by a further 9-17%, according to OECD. After that, who knows?

We are, in the words of Lydia Poole, post peak aid. The supply of aid dollars is down and will probably trend downwards from here, even as the climate crisis, conflict, and stuttering low-income economies mean that demand is trending up.

For decades, grants from aid agencies have been our go to engine for improving people’s lives around the world. Aid spend grew over 2.5x in 25 years, up from ~$90bn in 20001.

Now, those grants simply won’t be enough to meet the huge challenges we face. We need a new script for achieving social justice at scale, in a post peak-aid world.

Over the last few years, I’ve had a front-row seat to a generation of ventures making change happen, at scale (lucky me!). All of them began with grants2. And they are all now weaving bigger, deeper, more sustainable impact into the fabric of people’s lives and communities, without ongoing aid funding.

To me, those ventures are a point of inspiration.

Collectively, they gesture at an emerging playbook for getting to impact at scale. In this piece, I want to sketch this playbook in five steps. They are:

It’s easy to say that our ambition to make the world a better place need not shrink with global development budgets. The question is how to do that.

That’s what these plays are about.

But first, let me talk about why playbooks matter.

The danger of codifying ideas into an emerging playbook is that it becomes a rigid checklist. Reality is messy, so it goes without saying that not all five steps above apply to every product or service looking to create impact at scale. And certainly, the order is fluid (although I’d always suggest starting with #1).

Playbooks can be reductionist. They make people follow rules instead of thinking for themselves. So, why bother building them?

Because of the importance of the ‘default’3.

In other words, the importance of a sector-wide, shared mental model for how, in the majority of cases, we get from zero to impact at scale.

By starting to craft a playbook, we start to craft a new default for creating scalable, irreversible impact in a world with less aid funding.

The power of defaults is visible in how Silicon Valley has codified the science of scaling commercial startups. It starts with product-market fit (PMF). The startup shows traction through a range of widely known metrics: revenue run rate (RRR), average revenue per user (ARPU), lifetime value (LTV),the ratio of LTV to customer acquisition cost (CAC), and so on. Once you’ve demonstrated traction, you raise pre-seed, seed, and Series A, B, C and so on. The key is to bridge the valley of death, getting to sustainable revenue before your runway runs out. If you’re lucky to reach the other side of the valley, you might show hockey stick growth, and huge profitability.

There’s a default pathway to scale for commercial startups, with its own language (and acronyms), sketched out over the last three decades and exported worldwide. Founders, VCs, accelerators, startup employees, and everyone else in the ecosystem can use it as a rough guide, tracing proven steps as they grow. For Founders in particular, having a default gives you the means to benchmark yourself against others, to celebrate wins (raising a funding round, hitting a positive LTV:CAC ratio, etc), and to plan ahead with the map already sketched out.

Silicon Valley has built the default for scaling startups to massively profitable enterprises.

Now, let’s build the default for scaling new ideas to massive social change.

Those ideas might be from a startup. Or, they might come from a NGO, a government team, or a grassroots organisation.

Build products people love.

Anyone who sells a product directly to their user knows this. But as a general rule, the further you get from selling directly to your user, the less likely you are to build products people love.

If you sell an edtech product to a parent for their child, you’re still pretty close to your user.

If you sell a SaaS product to a CTO, to be used by her team, you’re less close.

And, if you sell products or services to aid agencies, to be used by their beneficiaries, you’re even less close than that.

This distance creates problems. One famous example is the One Laptop per Child’s $100 laptop. Built in the US (by people who’d never use them in their own lives or buy them for their own kids), and distributed via large international organisations and donor agencies, children and teachers found them difficult to use, easily broken, and not relevant to their learning needs.

It’s a similar story in tech for people with disabilities. During my time on the Assistive Tech Impact Fund (ATIF)4, I learnt that abandonment rates for products like wheelchairs, crutches, and prosthetics in sub-Saharan Africa were 50%. Half of users preferred using nothing at all to using the ugly, imported, mediocre products on offer.

Enter Koalaa. Koalaa designs and manufactures comfortable, soft-shell prosthetics for upper-limb amputees. Their goal is to make buying and wearing a prosthetic like wearing a sneaker: comfortable, easy, and fashionable. They’re an aspirational product. In fact, in 2023, Koalaa won the Tommy Hilfiger Fashion Frontier Challenge award.

Build products people love. It’s not just a nice sentiment. For Koalaa, it underpins their revenue model.

A user who loves his prosthetic becomes a lifelong customer. A typical Koalaa prosthetic costs US$75 per year. And they’ve found that even in the lowest-income countries, users are willing to pay at least $5 or $10 towards that, every year, for a product they love and use every day. Just like they’re also willing to pay for their smartphone and data bundle, or to lease their motorbike.

A government that sees users loving - and not abandoning - their prosthetic is also much more likely to contribute. After all, an amputee with a prosthetic they don’t abandon is much more likely to enter the workforce, and much more likely to live a productive, flourishing life. In Sierra Leone, the government both part-funded Koalaa’s prosthetics for low-income users, provided tax and import breaks, and a mandate for clinicians in primary health facilities to fit and provide aftercare. In total, these government subsidies covered ~$20 of the cost per year.

The Koalaa prosthetic you get in the UK, is - with some context-appropriate modifications like skin colour - almost the same as the one you’d get in Pakistan, or the US, or Sierra Leone. Whereas One Laptop per Child built a laptop for the 'developing world' that they knew wouldn’t fly in the US, Koalaa sells the same stylish, practical prosthetic all over the world. Where possible, they also cross-subsidise sales in lower-income countries with sales in higher-income ones.

For Koalaa, this blended revenue model takes all potential customers. They’ve also seen interest from businesses and cooperatives, buying prosthetics for employees and members.

And, of course, aid agencies and donors chip in too. But they do so as one of many revenue streams, which means a more resilient and sustainable revenue model for Koalaa, given shrinking aid budgets.

It starts with a product people love. When users actually pay for something, everyone else notices.

If I was to sum up this approach in a sentence, it would be: start by building products people love, then build a revenue model that holds you accountable to that. Those closer to the user - including the user themselves - will pay something if they love the product. It's a high bar, but it works. A compelling value proposition for the user, that leads to one revenue stream, becomes a compelling value proposition for others, and leads to multiple revenue streams.

Over 1 billion people need assistive technology today, projected to rise to 2 billion by 2050. This includes products like glasses, wheelchairs, and crutches that remain poorly designed and stigmatized for many people worldwide. I’m excited about what Koalaa might build next.

And, needless to say, it’s not just assistive tech where this holds true. One of the effects of large aid budgets and donors as primary customers for products like prosthetics was to create greater distance between user (sometimes called the beneficiary) and customer (aid agency). Shrinking aid budgets might actually force us to get closer to users.

Before moving on, there’s an important caveat. While you should always build products people love, it isn’t always ethical or practical to aim for revenue from the end user.

In Burkina Faso, Terre des Hommes have built a digital tool for health workers, supporting them to diagnose and treat malnourished children. Who’s the ethical, practical payer closest to the user? Certainly not households with starving children. And likely not health workers themselves. Could clinics or other health facilities contribute directly, through a subscription or outcomes-based agreement? This gets us revenue quickly, and gets us proof that a bespoke digital tool provides value above pen/paper or other existing solutions. It’s revenue and validation from close to the user, without extracting unethical payments from the user themselves.

I’m increasingly certain that giving low-income families the means to earn money is one of the most powerful engines for social change.

I met Manu a couple of years ago, while leading the scaling strategy curriculum for LSE’s 100x Impact Accelerator. Manu had joined the accelerator to scale Karya, his startup providing AI work opportunities for rural Indians on their smartphone5.

It takes seven generations of concerted effort for an Indian household on the poverty line to move to the middle class, with US$1500 of savings. Manu, one of the most brilliant minds I’ve met, short-circuited that by moving from rural India to Stanford to study computer science. But for many Indian families, the journey to financial wellbeing is relentless and the goal, if you get there at all, is decades away.

Karya splits big jobs from customers like Google (e.g. “build a training dataset in Marathi for our language model”) into micro-tasks (e.g. “speak and record set phrases in Marathi”). Then, it sends them to workers in rural India. For these tasks, workers get paid 20x the Indian minimum wage. What they do with that income is up to them. Manu has found that sending children to school, paying off debts, and buying basic household amenities are the most common ways families spend their extra income.

Product in, income out.

But there's something deeper here: product in, agency out.

Income gives you the means to do the things you want to do, and be the person you want to be. It gives you agency.

In Rwanda, I worked with Ampersand, an electric moto taxi startup. Their electric moto taxis netted Rwandese taxi drivers 30% more profit (due to the low price of charge relative to fuel)6.

In Zambia, I had the joy of supporting Wyson and Steve, an entrepreneur and civil servant pioneering pay-as-you-go bicycles for farmers. Using bicycles instead of walking gave farmers the ability to charge twice as much for milk, which hadn’t spoiled en route7. The work featured in the Guardian and BBC World Service. Originally funded by a £100K grant from the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), Wyson and Onyx Connect (his startup) have put thousands of bikes in the hands of farmers.

Product in, agency out.

Giving people income (and therefore agency) matters, even if nothing else follows.

Except, in our case, two things follow:

Product in, income out.

Product in, agency out.

You’ve built a product people love. If possible, you’ve improved users’ incomes, given them agency, and a better shot at affording your product or service.

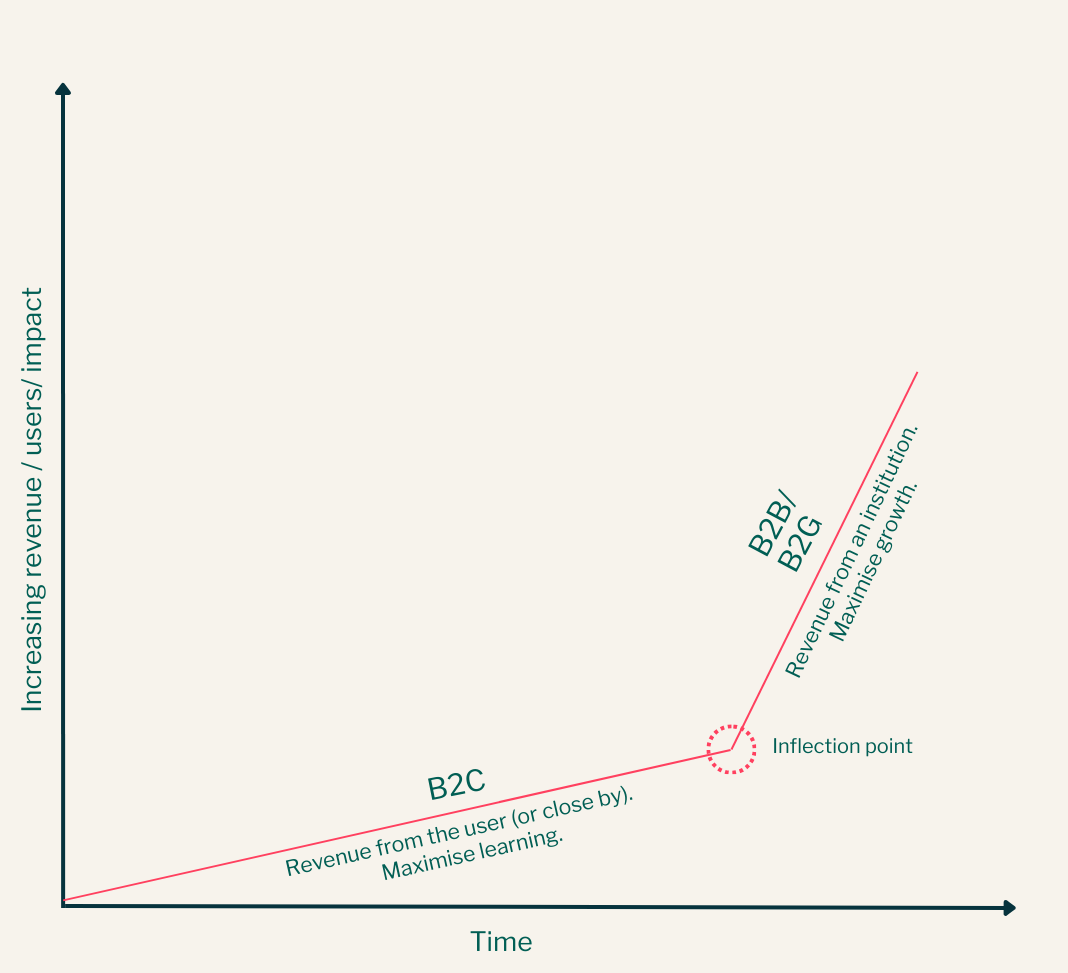

Now, to shift from impact to impact at scale, it’s likely you need to shift from a business-to-customer (B2C) to business-to-business (B2B) or business-to-government (B2G) revenue and delivery model. In simpler terms, your primary user and customer needs to shift from a person or household, to an institution.

To do that, you need to master what I call the institutional inflection point.

I’ve worked with tens of edtech startups now, across South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

One of those startups is Taleemabad, in Pakistan. Taleemabad has built a comprehensive edtech platform, providing teacher training, lesson plans, assessments, and data for policymakers and school leaders.

When Haroon started building Taleemabad, he went, product in hand, teacher to teacher, private school to private school, selling and onboarding.

At the same time, he knew that serving individual users wasn’t enough.

Pakistan, a country with ~100m children, is in the middle of an ‘education emergency’. 26m children are out of school. 45% of 10 year old students can’t read a simple Urdu story, and just 52% can’t solve a basic two-digit division problem.

Haroon recognised that truly tackling this crisis meant that, eventually, Taleemabad would have to become a part of the government’s education system. In concrete terms, that meant funding from Pakistani government rupees, service delivery by government personnel, and integration into public education supply chains, processes, and infrastructure.

So, from year one, they experimented relentlessly to understand how the government might adopt their platform. While going door to door to teachers and schools, Haroon also travelled across Pakistan to understand the government as a customer. In Haroon’s words, here’s some of the most important things they learnt and acted on:

To reiterate, Haroon committed deeply to two things at the same time: selling to, offering and learning about value to teachers and schools on the one hand, and throwing himself into the messy process of validating the government as the ultimate institutional customer on the other.

Journeys like Haroon’s gesture towards a pathway to large-scale impact. It looks something like this:

It’s much quicker to reach them without going to big institutions. This direct relationship maximises your learning about the product. It gives you the best shot at building something they love. It also provides you with some revenue. Grant funding can add some valuable fuel here, as it did for Taleemabad.

At the same time, you use as much of that revenue or funding as you can to learn about what it takes for you to become embedded in government systems8. At Brink, we call this being in “yes, if” mode: continuously testing and updating your beliefs about what it would take for a government (or other large institution) to buy into your idea.

Sometime (in my experience, around year 7), you hit an inflection point. As you enter government budgets and delivery mechanisms, revenue and # of users skyrockets. From the outside, the shift seems sudden. But you know it’s taken five, maybe ten years of groundwork. In Taleemabad’s case, after 7 years of working directly with schools, they’d reached 20K children. In 2024, their first year of government as a customer (but following years of behind-the-scenes sweat), they reached 136K. This year, they’ll reach 280K. Next year, they forecast reaching 690K.

In South Asia, education budgets make up 1.8% of GDP, or roughly ~$80bn per annum. In sub-Saharan Africa, that’s 3.5% of GDP and ~$68bn per annum. That’s a serious addressable market for initiatives that prove they help children learn.

Across sectors, institutional customers (especially governments, but also large NGOs, businesses, cooperatives, etc) can write you bigger cheques, and help you scale to radically more users in one swoop.

They’re more resilient too. Once a product like Taleemabad becomes a part of government budgets, processes and systems, their presence becomes hard to reverse. To borrow Silicon Valley parlance, Lifetime value (LTV) from the government as a customer is off the charts.

For Taleemabad, this means millions of children, teachers and communities can learn and teach better, for years to come.

Earlier, I talked about Wyson, who has put thousands of pay-as-you-go bikes in the hands of Zambian farmers.

Since starting in 2019, Wyson is approaching his own institutional inflection point. Rather than selling to individual users, Onyx Connect is increasingly selling to cooperatives (B2B).

In this model, ten, or fifty, or a hundred bikes are collectively leased to the head of a co-operative. In turn, the co-operative manages their bikes, allocating them to farmers, training them on riding the bikes, making simple fixes when they need to, and keeping track of payments. The co-operative pays a monthly fee, and generally gets to keep the bikes after two or three years.

Last time I caught up with Wyson, he said something that stuck with me: selling bikes to co-operatives was like learning a cheat code. All the complicated stuff - managing users, handling payments, fixing problems - suddenly became someone else's job.

I call this stewardship.

Stewardship is the management, delivery, and governance of the product or service. Wyson realised that the more you let go and spread stewardship around - the more you decentralise it - the bigger you can scale. It’s really difficult to have a deep, sustainable impact on millions of lives until you can find people with the incentive to take some of the load on your behalf.

In Wyson’s case, the steward (cooperative) mediated between Onyx Connect and the end user (farmer). They’re also experimenting with selling batches of bikes to employers, who provide them to their employees as a perk or means of commuting to work.

Stewards like cooperatives and employers can adapt the product or service to their user. Some cooperatives cover farmers if they miss the monthly payment. All in, decentralising stewardship improves your users’ experience while making that experience more scalable. In my experience, it’s one of the only ways to do both at the same time.

Broadly, overseas development aid has tended to the opposite path: treating users as passive beneficiaries, and concentrating management and delivery of products and services to them. At its worst, this centralised stewardship happens in a different country and context to the user (see: One Laptop per Child, described above). Post peak aid, we can try something different.

Or, to go right to the other end of the spectrum: you could decentralise stewardship all the way to your user, and her communities.

Take ABALOBI, a South African social enterprise. I came across them this year, as part of a scalomg bootcamp run by Enabel, Belgium’s agency for international co-operation. Enabel is funding 23 non-profits to scale new ideas in sub-Saharan Africa, and Brink is proud to serve as their scaling and experimentation partner.

ABALOBI, in collaboration with KU Leuven, equips fisher communities around river basins with sensor networks and a digital platform to monitor water quality and fish health. Communities own the data they generate, maintain the product, and use it to improve fishing practices, protect their environment, and advocate for change. They’ve even added training modules and weather reports, helping fishers make more income (see: step 2).

Once the product is in the hands of users, they own it, and they own the data they generate. What they do with both, is up to the community. Users - be it an individual or a small scale fishery - take on stewardship. They steward for as long as they keep deriving value.

ABALOBI has since expanded this model to Kenya, and (most recently) Tanzania, multiplying their impact, without sacrificing its depth, and without the need for massive organisation infrastructure.

.png)

So far, we’ve offered a recipe for scaling new ideas to more and more users, while retaining or even increasing the depth of impact.

Our final play takes this even further. To lock in impact at scale, ventures need to shift the culture. That is, they need to create change at the level of human language and behaviour, in a way that’s connected to but bigger than their product or service.

I was born in Pakistan, and lived there for half of my childhood. In English, the term ‘deaf’ has a narrow meaning, describing the medical condition for being unable to hear. In Urdu, ‘deaf’ (behra) is much more loaded. Deaf individuals are perceived as cognitively deficient; behra (deaf) is often paired with gunga, originally meaning mute but now more often meaning ‘stupid’ or ‘dumb’. The phrase ‘deaf and dumb’ (behra aur gunga) has solidified a stereotype in our culture.

Deaf Reach is on a mission to change that. Over the last three decades, they’ve built schools serving thousands of children across Pakistan. When I first started working with Richard, Sarah and the team, they told me about their three vectors for scaling. First, scaling across Pakistan. Their teachers took their curriculum, and turned it into bite-size videos in Pakistani Sign Language, so any deaf child in Pakistan could watch and learn. Second, scaling globally. Deaf Reach started to offer consulting services to grassroots organisations around the world serving deaf communities, to scale their expertise beyond Pakistan.

Over 30 years, their work has meant tens of thousands of deaf children fulfil their potential. At school, and then at work as adults, they show the rest of society the lunacy of equating deaf with dumb. And so, the third vector of scaling: shifting a culture to sever that connection.

That shift, as it emerges, will change everything. In the words of Richard, “if we can shift how deaf children are perceived, by themselves, their families, their communities and their country, our work is done”. Deaf children will be seen as worth investing in. It won’t just be Deaf Reach’s schools and videos who support them; everyone will. That’s impact at scale, nationwide, deep, and irreversible.

Earlier this year, I had the privilege of leading a study in Robotics for Global Development on behalf of the Frontier Tech Hub. There, I met Vimal, founder of Genrobotic Innovations in India. Genrobotics builds sewer-cleaning robots. His robots climb up and down manholes, and use their arms for picking, grabbing and shovelling movements. In India, like the rest of the world, manholes are mostly inspected, maintained and cleaned by humans, exposing them to hazardous climbs and harmful materials. Genrobotics automates this work, and retrains sewage workers to maintain the robots.

The word manhole implies manual labour, and since Genrobotic has existed Vimal has been on a mission to challenge this mindset. Through relentless campaigning, they compelled the Indian government to officially adopt the term “machine hole” in 2021 - a step towards redefining who cleans sewers and septic tanks.

In India, cleaning sewers is the fate of the lowest caste of workers. It’s a symbiotic relationship; the dirty, hazardous work reinforces the caste status in the eyes of their countrymen. Culture crystallises.

Just like Deaf Reach are severing the connection between deaf and dumb, Genrobotics are severing the connection between “lower caste” workers and sewage cleaning, elevating their right to a dignified and flourishing life.

Shifting the culture, slowly.

---

We’re post-peak aid, but we still need to take ideas to scale. It’s far from easy, but we’re already standing on the shoulders of giants. From there, we can see the pathway they’ve sketched: build products people love, improve their income, master institutions, transfer stewardship, shift culture. The rest is grit, luck, and execution.

Footnotes: